With over 68,842 downloads, one of my most successful Rust projects is a nondescript little program called mdbook-linkcheck. This is a link-checker for mdbook, the tool powering a lot of documentation in the Rust community, including The Rust Programming Language and The Rustc Dev Book.

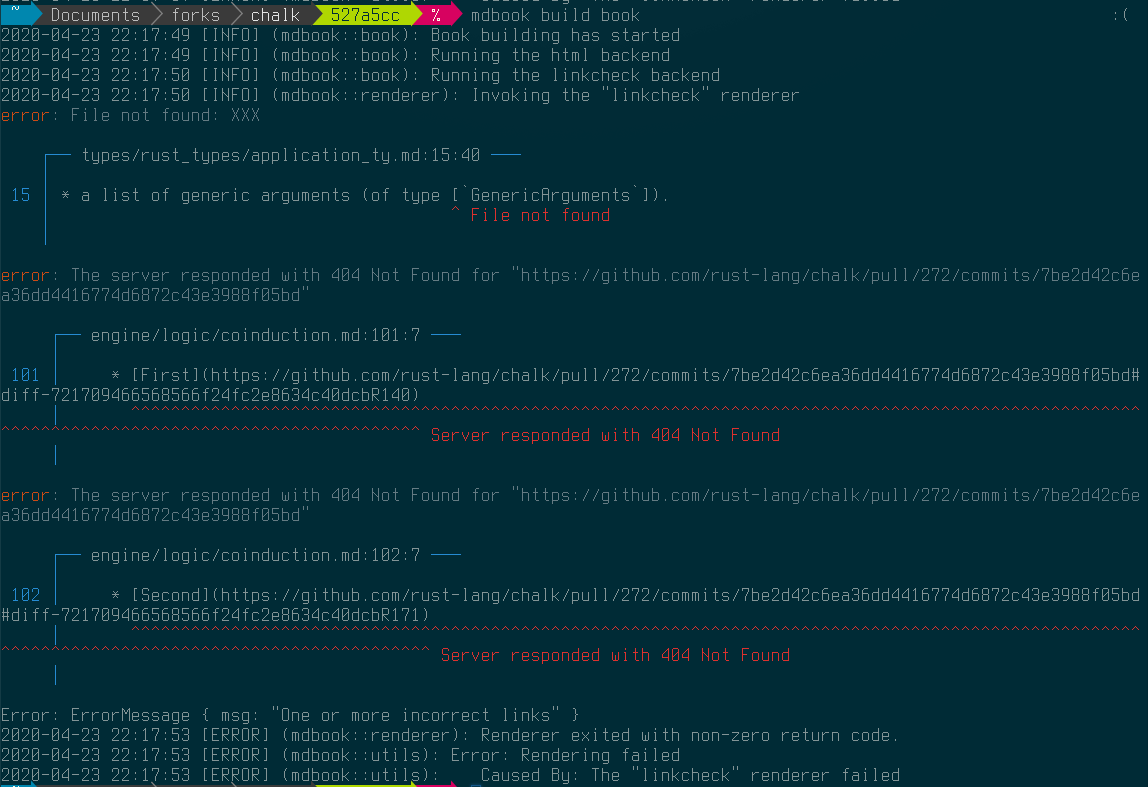

As an example of what it looks like, I recently found a couple broken links in the documentation for Chalk. When the tool detects broken links in your markdown it’ll emit error messages that point you at the place the link is defined and explain what the issue is.

This tool has been around for a while and works quite well, so when I was fixing a bug the other day I decided it’s about time to extract the core logic into a standalone library that others can use.

The code written in this article is available on GitHub and published [on crates.io][crate]. Feel free to browse through and steal code or inspiration.

If you found this useful or spotted a bug, let me know on the blog’s issue tracker!

What Belongs in a Library? Link to heading

When you start building a library it’s good to think about what problem the library is trying to solve. That way you know what features belong in the library and, more importantly, what doesn’t.

The linkcheck crate’s primary objective is to find links in a

document and check that they point to something valid. There seem to be two

concepts here:

Scanner- some sort of function which can consume text and return a stream of links that are found.Validator- something which can take a batch of links and tell you whether they are valid or not

For diagnostic purposes we’ll also want to know where each link occurs in

the source document. So instead of just being a String, a link will need to

drag its Span along with it.

The codespan crate contains a lot of powerful tools for

managing source code and emitting diagnostics, so I imagine I’ll be leaning

on it quite a bit.

In the long run, it’d be nice to include scanners for most popular formats, however to keep things manageable I’m going to constrain this to plain text and markdown for now. I imagine HTML would also be a nice addition because it’ll let people check their websites, but I’ll leave that as an exercise for later.

As far as I can tell, there are only really two types of links,

- Local Files - a link to another file on disk

- Web Links - a URL for some resource on the internet

Validating web links should be rather easy, we can send a GET request to the

appropriate website and our web client (probably reqwest) will let

us know if we’ve got a dead link or not.

Extracting Links from Plain Text Link to heading

I thought I’d start with plain text because that’s easiest. We want to create some sort of iterator which yields all the bits of text that resemble a URL.

Originally I thought it’d just be a case of writing a regular expression and

mapping the Matches iterator from the regex

crate, but it turns out URLs aren’t that easy to work with.

After searching google for about 10 minutes and scanning through dozens of

StackOverflow questions I wasn’t able to find an expression which would match

all the types of URLs I expected while also avoiding punctuation like a

trailing full stop or when a link is in parentheses, and detecting links

don’t have a scheme (e.g. ./README.md instead of file:///README.md).

This reminds me of a popular quote…

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think “I know, I’ll use regular expressions.” Now they have two problems.

Jamie Zawinski

Luckily for me, this problem has already been solved and the

linkify crate is available on crates.io!

Looking through the source code, it seems like they’ve written a lot of

manual code to take into account how URLs may be embedded in bodies of text.

This mainly consists of scanning for certain “trigger characters” (: for a

URL, @ for an email address) then backtracking to find the start of the

item. There are also lots of tests to make sure only the

desired text is detected as a match.

The end result means the implementation of our plaintext scanner is almost

trivial:

// src/scanners/plaintext.rs

use crate::codespan::Span;

use linkify::{LinkFinder, LinkKind};

pub fn plaintext(src: &str) -> impl Iterator<Item = (&str, Span)> + '_ {

LinkFinder::new()

.kinds(&[LinkKind::Url])

.links(src)

.map(|link| {

(

link.as_str(),

Span::new(link.start() as u32, link.end() as u32),

)

})

}

I also threw in tests for a couple examples:

// src/scanners/plaintext.rs

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::*;

#[test]

fn detect_urls_in_some_text() {

let src = "hello http://localhost/ world. this is file://some/text.";

let should_be = vec![

("http://localhost/", Span::new(6, 23)),

("file://some/text", Span::new(39, 55)),

];

let got: Vec<_> = plaintext(src).collect();

assert_eq!(got, should_be);

}

}

Extracting Links from Markdown Link to heading

For parsing markdown my go-to library is pulldown-cmark.

This exposes an iterator-based API, yielding Events like “start of

paragraph tag”, “end of inline code”, “horizontal rule”, and so on.

This API is pretty low level and you’ll need to do a lot of work yourself if you want to create some sort of semantic model (e.g. a DOM) of the document, but if you’re just wanting to scan through a document and extract specific bits like we are, it’s ideal.

The pulldown-cmark parser also provides an “offset”

iterator who’s Item is a (Event<'a>, Range<usize>). This should give us enough information to provide developers

with useful diagnostics.

My initial markdown scanner looked something like this:

// src/scanners/markdown.rs

pub fn markdown(src: &str) -> impl Iterator<Item = (String, Span)> + '_ {

Parser::new(src)

.into_offset_iter()

.filter_map(|(event, range)| match event {

Event::Start(Tag::Link(_, dest, _))

| Event::Start(Tag::Image(_, dest, _)) => Some((

dest.to_string(),

Span::new(range.start as u32, range.end as u32),

)),

_ => None,

})

}

The chain of iterator combinators and match statement make the code look

complicated, the idea itself is quite simple… Filter out everything but the

start of Link and Image tags, then transform them to a tuple containing

the link itself and its location in the source text.

The pulldown-cmark parser also lets you provide a callback that can will be

triggered whenever it encounters a footnote-style link (e.g. [some text][link]) with no corresponding link definition (e.g. [link]: https://example.com). This is normally meant as a mechanism for fixing the

broken reference, but we can use it to emit diagnostics.

The updated scanner:

// src/scanners/markdown.rs

use crate::codespan::Span;

use pulldown_cmark::{Event, Options, Parser, Tag};

pub fn markdown(src: &str) -> impl Iterator<Item = (String, Span)> + '_ {

markdown_with_broken_link_callback(src, &|_, _| None)

}

pub fn markdown_with_broken_link_callback<'a, F>(

src: &'a str,

on_broken_link: &'a F,

) -> impl Iterator<Item = (String, Span)> + 'a

where

F: Fn(&str, &str) -> Option<(String, String)>,

{

Parser::new_with_broken_link_callback(

src,

Options::ENABLE_FOOTNOTES,

Some(on_broken_link),

)

.into_offset_iter()

.filter_map(|(event, range)| match event {

Event::Start(Tag::Link(_, dest, _))

| Event::Start(Tag::Image(_, dest, _)) => Some((

dest.to_string(),

Span::new(range.start as u32, range.end as u32),

)),

_ => None,

})

}

Unfortunately, the on_broken_link callback doesn’t provide span information

so that’ll make it a bit tricky to provide useful error messages.

I had to deal with this in mdbook-linkcheck as well and ended up using a

hacky workaround consisting of a call to

src.index_of(broken_reference) and hoping for the best.

Hopefully raphlinus/pulldown-cmark#165 will be solved some time soon and they’ll change the signature to something more useful, because it’s kinda clunky at the moment. I’ve seen at least one case where these sorts of broken links occur in real world documents, so it’d be nice to have a solid solution.

By now you’ve probably identified a pattern with implementing scanners.

Basically,

- Find a crate that already exists

- let them do the hard work of parsing your document

- do a bit of post-processing to extract just the bits we care about

Validating Links to Local Files Link to heading

The main reason we want to check links to other local files is for

documentation tools like mdbook. This is where several markdown

files exist in a directory tree, and they will be compiled to HTML that

maintains the same tree structure.

Constraints Link to heading

It’s important to re-state this mdbook-specific aspect because it adds a couple interesting constraints to the problem…

- You can write a link to a directory (e.g.

/foo/) and the browser will fall back to a default path (e.g./foo/index.html) - There is the concept of a “root directory” which the document will be served

from, and any absolute links (i.e. a link starting with a

/) should be relative to this directory - We want to control whether links can go outside the root directory (e.g.

../../../../etc/passwd) for security reasons and because these sorts of links make assumptions about the environment which may not always be true (e.g. the relative location of two repositories on disk)

These constraints are encapsulated in our Options type:

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

use std::{ffi::OsString, path::PathBuf};

pub struct Options {

root_directory: Option<PathBuf>,

default_file: OsString,

links_may_traverse_the_root_directory: bool,

}

impl Options {

pub const DEFAULT_FILE: &'static str = "index.html";

pub fn new() -> Self {

Options {

root_directory: None,

default_file: OsString::from(Options::DEFAULT_FILE),

links_may_traverse_the_root_directory: false,

}

}

}

(The type also has several getters and setters, but they are largely irrelevant for our purposes)

The first big operation that we can do with Options is to “join” a directory

and a link. This reduces to a current_dir.join(second) in the simplest case,

but we need to do some fancy logic when the link is absolute.

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

impl Options {

fn join(

&self,

current_dir: &Path,

second: &Path,

) -> Result<PathBuf, Reason> {

if second.is_absolute() {

// if the path is absolute (i.e. has a leading slash) then it's

// meant to be relative to the root directory, not the current one

match self.root_directory() {

Some(root) => {

let mut buffer = root.to_path_buf();

// append everything except the root element

buffer.extend(second.iter().skip(1));

Ok(buffer)

},

// You really shouldn't provide links to absolute files on your

// system (e.g. "/home/michael/Documents/whatever" or

// "/etc/passwd").

//

// For one, it's extremely brittle and will probably only work

// on that computer, but more importantly it's also a vector

// for directory traversal attacks.

//

// Feel free to send a PR if you believe otherwise.

None => Err(Reason::TraversesParentDirectories),

}

} else {

Ok(current_dir.join(second))

}

}

}

The next big operation is path canonicalisation. This is where we convert the

joined path to its canonical form, resolving symbolic links and ..s

appropriately. As a side-effect of canonicalisation, the OS will also return a

FileNotFound error if the item doesn’t exist.

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

impl Options {

fn canonicalize(&self, path: &Path) -> Result<PathBuf, Reason> {

let mut canonical = path.canonicalize()?;

if canonical.is_dir() {

canonical.push(&self.default_file);

// we need to canonicalize again because the default file may be a

// symlink, or not exist at all

canonical = canonical.canonicalize()?;

}

Ok(canonical)

}

}

We also need to do a quick sanity check to make sure links don’t escape the “root” directory unless explicitly allowed.

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

impl Options {

fn sanity_check(&self, path: &Path) -> Result<(), Reason> {

if let Some(root) = self.root_directory() {

if !(self.links_may_traverse_the_root_directory || path.starts_with(root))

{

return Err(Reason::TraversesParentDirectories);

}

}

Ok(())

}

}

Resolving File System Links Link to heading

Now we’ve encoded our constraints in the Options type, we can wrap all this

code up into a single function. This function will take a “link” and tries to

figure out which file is being linked to.

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

pub fn resolve_link(

current_directory: &Path,

link: &Path,

options: &Options,

) -> Result<PathBuf, Reason> {

let joined = options.join(current_directory, link)?;

let canonical = options.canonicalize(&joined)?;

options.sanity_check(&canonical)?;

// Note: canonicalizing also made sure the file exists

Ok(canonical)

}

As a side note, we use the thiserror crate to simplify the

boilerplate around defining the reason that validation may fail, Reason. Our

Reason type is just an enum of the different reasons that validation may fail.

// src/validation/mod.rs

/// Possible reasons for a bad link.

#[derive(Debug, thiserror::Error)]

#[non_exhaustive]

pub enum Reason {

#[error("Linking outside of the book directory is forbidden")]

TraversesParentDirectories,

#[error("An OS-level error occurred")]

Io(#[from] std::io::Error),

#[error("The web client encountered an error")]

Web(#[from] reqwest::Error),

}

impl Reason {

pub fn file_not_found(&self) -> bool {

match self {

Reason::Io(e) => e.kind() == std::io::ErrorKind::NotFound,

_ => false,

}

}

pub fn timed_out(&self) -> bool {

match self {

Reason::Web(e) => e.is_timeout(),

_ => false,

}

}

}

Wrapping It Up in a Check Link to heading

The whole point of this endeavour is to have some sort of validation function which takes a link to a local file and makes sure it’s valid.

For this, I’m going to introduce the idea of a validator context. This is a collections of useful properties and callbacks to help guide the validation process.

At the moment we only need access to the file system validator’s Options, so

the Context trait looks a little bare.

// src/validation/mod.rs

pub trait Context {

/// Options to use when checking a link on the filesystem.

fn filesystem_options(&self) -> &Options;

}

Now we need to wrap our resolve_link() in a check_filesystem() function

which uses the Context

// src/validation/filesystem.rs

use crate::validation::Context;

/// Check whether a [`Path`] points to a valid file on disk.

///

/// If a fragment specifier is provided, this function will scan through the

/// linked document and check that the file contains the corresponding anchor

/// (e.g. markdown heading or HTML `id`).

pub fn check_filesystem<C>(

current_directory: &Path,

path: &Path,

fragment: Option<&str>,

ctx: &C,

) -> Result<(), Reason>

where

C: Context,

{

log::debug!(

"Checking \"{}\" in the context of \"{}\"",

path.display(),

current_directory.display()

);

let resolved_location = resolve_link(

current_directory,

path,

ctx.filesystem_options(),

)?;

log::debug!(

"\"{}\" resolved to \"{}\"",

path.display(),

resolved_location.display()

);

if let Some(fragment) = fragment {

// TODO: detect the file type and check the fragment exists

log::warn!(

"Not checking that the \"{}\" section exists in \"{}\" because fragment resolution isn't implemented",

fragment,

resolved_location.display(),

);

}

Ok(())

}

The code isn’t overly exciting, it boils down to a bunch of log statements and

returns a () instead of PathBuf to indicate we don’t care about the result

of a successful check.

You may have noticed there’s this new fragment parameter and a big TODO

comment when one is provided.

The idea is that sometimes we won’t just have a link to some document (e.g.

../index.md) and will want to link to a particular part of the document. In

HTML this is often done using a fragment identifier, the some-heading

part in ../index.md#some-heading.

I’m not really sure how I’ll implement this one. Different document types

will implement fragment identifiers in different ways, so I’d probably need

to check the linked file’s mime-type and search for an element with a

id="some-heading" attribute in HTML, or a markdown heading who’s

slug looks something like some-heading… That sounds a bit fiddly,

so I’m going to skip it for now.

Validating Links on the Web Link to heading

Now we’ve reached the core part of our link checker, checking if a URL points to a valid resource on the internet.

The good news is that actually checking that a URL is valid is almost trivial.

The reqwest crate provides an asynchronous HTTP client with a nice

API, so checking the URL is as simple as sending a GET request.

// src/validation/web.rs

use http::HeaderMap;

use reqwest::{Client, Url};

/// Send a GET request to a particular endpoint.

pub async fn get(

client: &Client,

url: &Url,

extra_headers: HeaderMap,

) -> Result<(), reqwest::Error> {

client

.get(url.clone())

.headers(extra_headers)

.send()

.await?

.error_for_status()?;

Ok(())

}

Something to note is that we accept this extra_headers parameter. Sometimes

you’ll need to send extra headers to particular endpoints (imagine needing to

send Authorization: bearer some-token to access a page that requires

logging in), so we’ll give the caller a way to do that.

From a performance standpoint it’s also nice to know creating an empty

HeaderMap won’t make any allocations. I doubt we’d even notice/care

if it did, but it’s still nice to know.

Caching Link to heading

While sending a GET request to a particular URL is easy to do, going with

just the naive version (for link in links { check(link) }) will make the

link checking process incredibly slow.

What we want to do is avoid unnecessary trips over the network by reusing previous results, both from within the same run (e.g. a file links to the same URL twice) or from multiple runs (e.g. the last time link checking was done in CI).

We’ll need some sort of caching layer.

To see why this is important, let’s have a look at how many web links there are in some of the books on my computer.

# The Rust Programming Language (aka "The Book")

$ cd ~/Documents/forks/book

$ rg 'http(s?)://' --stats --glob '*.md' --quiet

421 matches

415 matched lines

330 files contained matches

430 files searched

# The Rust developers guide

$ cd ~/Documents/forks/rustc-guide

$ rg 'http(s?)://' --stats --glob '*.md' --quiet

566 matches

558 matched lines

79 files contained matches

102 files searched

The mdbook-linkcheck plugin is executed whenever a mdbook book is built

and I know Rust is fast, but the network is slow and making 400-500 web

requests every time you make a change is quickly going to make the link

checker unusable.

To mix things up a little I’m going to show you the final check_web()

function and we can step through it bit by bit.

// src/validation/web.rs

/// Check whether a [`Url`] points to a valid resource on the internet.

pub async fn check_web<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C) -> Result<(), Reason>

where

C: Context,

{

log::debug!("Checking \"{}\" on the web", url);

if already_valid(&url, ctx) {

log::debug!("The cache says \"{}\" is still valid", url);

return Ok(());

}

let result = get(ctx.client(), &url, ctx.url_specific_headers(&url)).await;

if let Some(fragment) = url.fragment() {

// TODO: check the fragment

log::warn!("Fragment checking isn't implemented, not checking if there is a \"{}\" header in \"{}\"", fragment, url);

}

let entry = CacheEntry::new(SystemTime::now(), result.is_ok());

update_cache(url, ctx, entry);

result.map_err(Reason::from)

}

The first interesting bit is the already_valid() check. This runs beforehand

and lets us skip any further work if our cache says the link is already valid.

// src/validation/web.rs

fn already_valid<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C) -> bool

where

C: Context,

{

if let Some(cache) = ctx.cache() {

return cache.url_is_still_valid(url, ctx.cache_timeout());

}

false

}

What we do is check if the Context has a cache (for simplicity, some users

may not care about caching) and then ask the cache to do a lookup, specifying

how long a cache entry can be considered valid for.

The Cache itself isn’t anything special. It’s just a wrapper around a

HashMap.

// src/validation/mod.rs

use reqwest::Url;

use std::{collections::HashMap, time::SystemTime};

pub struct Cache {

entries: HashMap<Url, CacheEntry>,

}

pub struct CacheEntry {

pub timestamp: SystemTime,

pub valid: bool,

}

The Cache::url_is_still_valid() method is a bit more complex because we

need to deal with the fact that you can sometimes time travel when using

SystemTime (e.g. because your computer’s clock changed between now and

whenever the CacheEntry was added).

impl Cache {

pub fn url_is_still_valid(&self, url: &Url, timeout: Duration) -> bool {

if let Some(entry) = self.lookup(url) {

if entry.valid {

if let Ok(time_since_check_was_done) = entry.timestamp.elapsed()

{

return time_since_check_was_done < timeout;

}

}

}

false

}

pub fn lookup(&self, url: &Url) -> Option<&CacheEntry> {

self.entries.get(url)

}

}

Something to note is that this cache is deliberately conservative. It’ll only

consider an entry to “still be valid” if it was previously valid and there

have been no time-travelling shenanigans. We also need a timeout parameter

to allow for cache invalidation.

To facilitate caching, the Context trait will need a couple more methods:

// src/validation/mod.rs

pub trait Context {

...

/// An optional cache that can be used to avoid unnecessary network

/// requests.

///

/// We need to use internal mutability here because validation is done

/// concurrently. This [`MutexGuard`] is guaranteed to be short lived (just

/// the duration of a [`Cache::insert()`] or [`Cache::lookup()`]), so it's

/// okay to use a [`std::sync::Mutex`] instead of [`futures::lock::Mutex`].

fn cache(&self) -> Option<MutexGuard<Cache>> { None }

/// How long should a cached item be considered valid for before we need to

/// check again?

fn cache_timeout(&self) -> Duration {

// 24 hours should be a good default

Duration::from_secs(24 * 60 * 60)

}

}

Next up is a call to the get() function we wrote earlier.

// src/validation/web.rs

pub async fn check_web<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C) -> Result<(), Reason>

where

C: Context,

{

...

let result = get(ctx.client(), &url, ctx.url_specific_headers(&url)).await;

...

}

We want to reuse the same HTTP client if possible because we get nice things

like connection pooling and the ability to set headers that’ll be sent with

every request (e.g. User-Agent). We also need to ask the Context if there

are any headers that need to be sent when checking this specific URL.

*sigh*… Okay, let’s add some more methods to the Context trait.

// src/validation/mod.rs

pub trait Context {

...

/// The HTTP client to use.

fn client(&self) -> &Client;

/// Get any extra headers that should be sent when checking this [`Url`].

fn url_specific_headers(&self, _url: &Url) -> HeaderMap { HeaderMap::new() }

}

You’ll also notice that we store the return value from get() in a result

variable instead of using ? to bail if an error occurs. That’s necessary for

the next bit… updating the cache.

// src/validation/web.rs

pub async fn check_web<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C) -> Result<(), Reason>

where

C: Context,

{

...

let entry = CacheEntry::new(SystemTime::now(), result.is_ok());

update_cache(url, ctx, entry);

...

}

fn update_cache<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C, entry: CacheEntry)

where

C: Context,

{

if let Some(mut cache) = ctx.cache() {

cache.insert(url.clone(), entry);

}

}

Updating the cache isn’t overly interesting, we just create a new CacheEntry

and add it to the cache if the Context has one.

And finally we can return the result, converting the reqwest::Error from

get() into a Reason.

// src/validation/web.rs

pub async fn check_web<C>(url: &Url, ctx: &C) -> Result<(), Reason>

where

C: Context,

{

...

result.map_err(Reason::from)

}

Tying it All Together Link to heading

Now we’ve implemented a couple validators it’s time to give users a more

convenient interface. Ideally, I’d like to provide a single asynchronous

validate() function that accepts a list of links and a Context, and returns

a summary of all the checks.

This turned out to be kinda annoying because one of our validators is asynchronous and the other isn’t. It’s not made easier by needing to deal with all the different possible outcomes of link checking, including…

- valid - the check passed successfully

- invalid - the check failed for some

Reason - unknown link type - we can’t figure out which validator to use, and

- ignored - sometimes users will want to skip certain links (e.g. to skip false positives, or because the server on the other end is funny)

For reference, a Link is just a string containing the link itself, plus

some information we can use to figure out which text it came from (e.g. to

provide pretty error messages).

// src/lib.rs

/// A link to some other resource.

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq)]

pub struct Link {

/// The link itself.

pub href: String,

/// Where the [`Link`] lies in its source text.

pub span: Span,

/// Which document does this [`Link`] belong to?

pub file: FileId,

}

Categorising Links Link to heading

To figure out which validator to use, we’ll need to sort links into categories.

// src/lib.rs

use std::path::PathBuf;

use reqwest::Url;

enum Category {

/// A local file.

FileSystem {

path: PathBuf,

fragment: Option<String>,

},

/// A URL for something on the web.

Url(Url),

}

From my work with mdbook-linkcheck I know categorising can be kinda annoying,

so let’s create a couple tests.

// src/lib.rs

#[test]

fn parse_into_categories() {

let inputs = vec![

(

"https://example.com/",

Some(Category::Url(

Url::parse("https://example.com/").unwrap(),

)),

),

(

"README.md",

Some(Category::FileSystem {

path: PathBuf::from("README.md"),

fragment: None,

}),

),

(

"./README.md",

Some(Category::FileSystem {

path: PathBuf::from("./README.md"),

fragment: None,

}),

),

(

"./README.md#license",

Some(Category::FileSystem {

path: PathBuf::from("./README.md"),

fragment: Some(String::from("license")),

}),

),

];

for (src, should_be) in inputs {

let got = Category::categorise(src);

assert_eq!(got, should_be);

}

}

Luckily, reqwest::Url implements std::str::FromStr so we can just use

some_string.parse() for the Url variant.

// src/lib.rs

impl Category {

fn categorise(src: &str) -> Option<Self> {

if let Ok(url) = src.parse() {

return Some(Category::Url(url));

}

...

}

}

If parsing it as a Category::Url fails it’s probably going to fall into the

FileSystem category. We can’t reuse something like the reqwest::Url or

http::Uri types because they both expect the URL/URI to have a schema so

we’ll need to get creative.

Regardless of whether we check fragments for file system links or not, we’ll

need to make sure we can handle links with fragments otherwise we’ll try to

see if the ./README.md#license file exists when we actually meant

./README.md.

The first step in parsing file system links is to split it into path and

fragment bits.

// src/lib.rs

impl Category {

fn categorise(src: &str) -> Option<Self> {

...

let (path, fragment) = match src.find("#") {

Some(hash) => {

let (path, rest) = src.split_at(hash);

(path, Some(String::from(&rest[1..])))

},

None => (src, None),

};

...

}

}

Something else to consider is that the path may be URL-encoded (e.g.

because the file’s name contains a space). Because I’m lazy, instead of

pulling in a crate for URL decoding I’m going to reuse the same machinery the

http crate uses for parsing the path section of a URL…

http::uri::PathAndQuery.

// src/lib.rs

impl Category {

fn categorise(src: &str) -> Option<Self> {

...

// as a sanity check we use the http crate's PathAndQuery type to make

// sure the path is decoded correctly

if let Ok(path_and_query) = path.parse::<PathAndQuery>() {

return Some(Category::FileSystem {

path: PathBuf::from(path_and_query.path()),

fragment,

});

}

...

}

}

And that should be enough to categorise a link.

Full code for Category::categorise().

impl Category {

fn categorise(src: &str) -> Option<Self> {

if let Ok(url) = src.parse() {

return Some(Category::Url(url));

}

let (path, fragment) = match src.find("#") {

Some(hash) => {

let (path, rest) = src.split_at(hash);

(path, Some(String::from(&rest[1..])))

},

None => (src, None),

};

// as a sanity check we use the http crate's PathAndQuery type to make

// sure the path is decoded correctly

if let Ok(path_and_query) = path.parse::<PathAndQuery>() {

return Some(Category::FileSystem {

path: PathBuf::from(path_and_query.path()),

fragment,

});

}

None

}

}

Validating a Single Link Link to heading

Now we need to write a function that will match on the Category and invoke

the appropriate validator.

When a link fails validation we’ll tell the caller by returning the name of the

failing link and why it failed (InvalidLink).

// src/validation/mod.rs

/// A [`Link`] and the [`Reason`] why it is invalid.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct InvalidLink {

/// The invalid link.

pub link: Link,

/// Why is this link invalid?

pub reason: Reason,

}

I’m also going to need an intermediate type representing the different possible outcomes.

// src/validation/mod.rs

enum Outcome {

Valid(Link),

Invalid(InvalidLink),

Ignored(Link),

UnknownCategory(Link),

}

Now we can start writing our validate_one() function.

// src/validation/mod.rs

/// Try to validate a single link, deferring to the appropriate validator based

/// on the link's [`Category`].

async fn validate_one<C>(

link: Link,

current_directory: &Path,

ctx: &C,

) -> Outcome

where

C: Context,

{

unimplemented!()

}

Users need the ability to skip a link if desired, so let’s give Context a

should_ignore() method and call it at the top of validate_one().

// src/validation/mod.rs

pub trait Context {

...

/// Should this [`Link`] be skipped?

fn should_ignore(&self, _link: &Link) -> bool { false }

}

async fn validate_one<C>(

link: Link,

current_directory: &Path,

ctx: &C,

) -> Outcome

where

C: Context,

{

if ctx.should_ignore(&link) {

log::debug!("Ignoring \"{}\"", link.href);

return Outcome::Ignored(link);

}

...

}

And now comes the big ugly match statement for dispatching to the appropriate

validator.

// src/validation/mod.rs

async fn validate_one<C>(

link: Link,

current_directory: &Path,

ctx: &C,

) -> Outcome

where

C: Context,

{

...

match link.category() {

Some(Category::FileSystem { path, fragment }) => Outcome::from_result(

link,

check_filesystem(

current_directory,

&path,

fragment.as_deref(),

ctx,

),

),

Some(Category::Url(url)) => {

Outcome::from_result(link, check_web(&url, ctx).await)

},

None => Outcome::UnknownCategory(link),

}

}

The astute amongst you may have noticed that the check_filesystem() function

is synchronous and will need to do some interaction with the file system…

Which may block, especially if we might be reading the file’s contents to

check that a fragment identifier is valid.

Normally we get taught that doing something that may block is a big no-no when writing asynchronous code.

And yeah, technically I’d agree with that sentiment… But practically speaking you probably won’t notice the difference.

If we don’t need check fragments, a call to check_filesystem() won’t need

much more than a couple calls to stat(2). Even if we did need to

scan through a file to find the section identified by a fragment you can

expect file system links to point at reasonably sized files (e.g. less than

1MB) and reasonably close (i.e. not on a network drive on the other side of

the world).

All of this means that we won’t block for very long (maybe 10s of milliseconds at worst?) and the link checker will still be making progress, plus if link-checking will be slow if we’re going over the network anyway, so… she’ll be right?

Validating Bulk Links Link to heading

The final step in creating a high-level validate() function is to actually

write it.

We can implement a buffered fan-out, fan-in flow by leveraging

[StreamExt::buffer_unordered()][buffer_unordered] adapter to run up to n

validations concurrently, then use `StreamExt::collect() to merge

the results.

// src/validation/mod.rs

/// Validate several [`Link`]s relative to a particular directory.

pub fn validate<'a, L, C>(

current_directory: &'a Path,

links: L,

ctx: &'a C,

) -> impl Future<Output = Outcomes> + 'a

where

L: IntoIterator<Item = Link>,

L::IntoIter: 'a,

C: Context,

{

futures::stream::iter(links)

.map(move |link| validate_one(link, current_directory, ctx))

.buffer_unordered(ctx.concurrency())

.collect()

}

The function signature looks pretty gnarly because we’re wanting to accept

anything which can be turned into an iterator that yields Links (e.g. a

Vec<Link> or one of the scanner iterators), but other than that it’s rather

straightforward.

- Convert the synchronous iterator into a

futures::Stream - Map each

Linkto an unstarted future which will validate that link - Make sure we poll up to

ctx.concurrency()futures to completion concurrently withbuffer_unordered() - Collect the results into one container

We have almost everything we need, too. The only necessary additions are some

sort of bucket for Outcomes (called Outcomes), and a way for Context to

control how many validations are polled to completion at a time.

// src/validation/mod.rs

pub trait Context {

...

/// How many items should we check at a time?

fn concurrency(&self) -> usize { 64 }

}

/// The result of validating a batch of [`Link`]s.

#[derive(Debug, Default)]

pub struct Outcomes {

/// Valid links.

pub valid: Vec<Link>,

/// Links which are broken.

pub invalid: Vec<InvalidLink>,

/// Items that were explicitly ignored by the [`Context`].

pub ignored: Vec<Link>,

/// Links which we weren't able to identify a suitable validator for.

pub unknown_category: Vec<Link>,

}

impl Extend<Outcome> for Outcomes {

fn extend<T: IntoIterator<Item = Outcome>>(&mut self, items: T) {

for outcome in items {

match outcome {

Outcome::Valid(v) => self.valid.push(v),

Outcome::Invalid(i) => self.invalid.push(i),

Outcome::Ignored(i) => self.ignored.push(i),

Outcome::UnknownCategory(u) => self.unknown_category.push(u),

}

}

}

}

And yeah, that’s all there is to it. Pretty easy, huh?

Conclusions Link to heading

This took a bit longer than I expected to walk through, but hopefully you’ve now

got a good idea of how the linkcheck crate works 🙂

Overall it wasn’t too difficult to implement, although it took a couple iterations until I found a way to merge the different validators that worked… My first attempt at integrating synchronous and asynchronous validators, all of which have their own sets of inputs and expectations, led to some rather ugly code.

It kinda reminds me of an article called “What Colour is Your Function?” by Bob Nystrom…

Bob makes a good case that having a sync/async split in your language (like Rust, Python, or Node) can lead to poor ergonomics and difficulty reusing code. He also points out that it’s possible to have both a single “mode” of execution and all the nice things that come along with async code. Go’s green threading (“goroutines”) are a really good example of this.