Motivation is a funny thing.

I’m someone who’s productivity levels change wildly depending on my motivation levels. When I work on something which I’m passionate about or which interests me on an intellectual level (e.g. computational geometry or systems programming), I’m routinely 5-10x more productive than my peers.

However, if I’m working on something which is less personally interesting (e.g. tracking down GUI bugs or creating yet another CRUD app) I’ll tend to drag my feet and not work as hard.

I’m sure this revelation isn’t overly profound. Although the amount of variation may change from person to person, most people’s productivity will ebb and flow with their motivation levels. Society typically labels the flatter, more consistent people as being “disciplined”, while those with more volatile productivity levels are considered “lazy geniuses”.

With most people working remotely due to the recent pandemic, I’ve had an opportunity to do some introspection and realised that for the last month or so I’ve been in one of those low motivation periods.

The engineer in me wants to find out why, and what I can do to fix it.

While I’m using the term “productivity”, this doesn’t necessarily mean the amount of work done at my day job.

Yes, that plays a big part in productivity (because it’s where I spend most of my daylight hours through the week), but I’m also referring to the things I do in my spare time like toy projects, thought experiments, and personal development.

Inspiration Link to heading

A lot of the projects or writing I do in my spare time can be traced back to problems or observations I’ve encountered at my day job.

For example, I might notice some unnecessary manual work in our release process and create a Rust library which could make this easier, or I may have needed to add a feature for line simplification to our product and decide to also implement it in a side project.

I’m always very careful to stick with openly available information (e.g. the Line Simplification article mainly draws from Wikipedia) and not expose sensitive intellectual property, but that doesn’t mean you can’t use the problems you encounter at work as inspiration for original research.

Now that the major project I’ve been working on for the last year is entering its final phases, I feel like a lot of those initial sources of inspiration have started to dry up. Sure, this product will be in the wild for quite a while and we’ll be continuing to develop it, but I can’t foresee many game changing new challenges or features.

This means I’ll need to find a new source of inspiration, potentially something not related to work, or maybe by transitioning to a different area within my company/industry.

The Learning Curve Link to heading

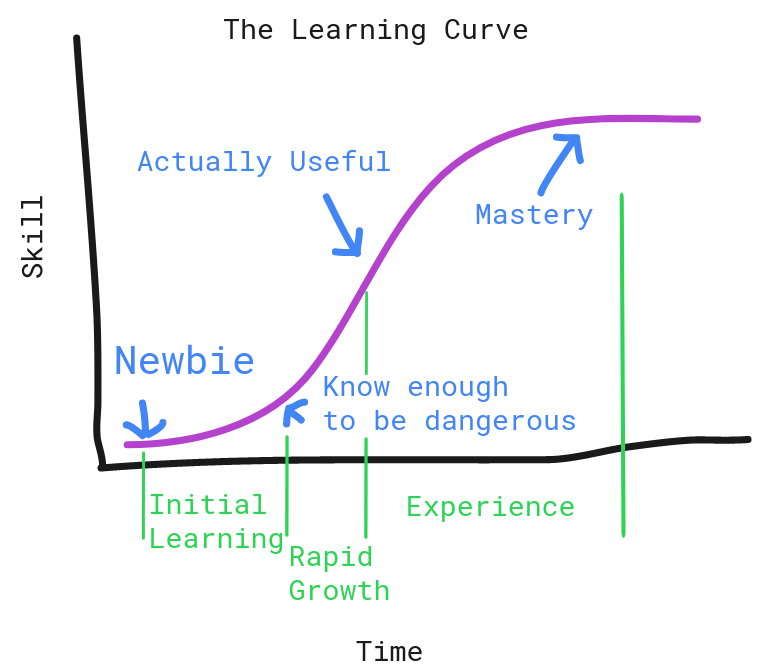

The Learning Curve is a model of how a person’s skill/competence in a particular topic increases with practice.

When displayed visually, it looks something like this:

Visual representation of the learning curve

As you can see from my highly scientific diagram, there are 3 phases you’ll pass through as you practice a skill,

- Initial Learning - this is where you learn the basics (how to declare a variable, what is a loop, etc.)

- Rapid Growth - in this phase you’ve got a grasp of the basics and go through a big growth spurt as you realise all the cool things you can do with this new-found knowledge

- Experience - this is where you start applying the knowledge you’ve learned and can begin practising it professionally

Each phase has a different effect on the psyche and a person’s motivation levels.

For example, as a newbie everything will be unfamiliar and confusing, and there’s a strong temptation to give up, or you may feel that it’s not for you. This is one of the reasons you tend to get a large number of drop-outs in the first year of a university degree.

Once you’ve grasped the basics you know enough to be dangerous. I’m sure we’ve all met someone who’s at this point, they are able to understand the domain-specific jargon or concepts and in their enthusiasm they feel like they’re an expert on the topic, wanting to share all the new knowledge they’ve gained.

This phase tends to be really fun, you start to get a deeper understanding of the topic and its full potential.

Finally, you are competent enough to start applying your knowledge in a productive way and start gaining the experience that differentiates masters from the rest.

In this phase you may only gain a small amount of competence, but each piece of knowledge is hard-won and tends to be incredibly advanced or domain-specific. You’ve also reached the point where the Rapid Growth phase’s enthusiasm is started to wear off as things which were previously novel and mind-boggling become commonplace.

Not many get this far.

In terms of my own development, I’d say I’ve passed the Actually Useful point and am starting to plateau out, at least in the areas of C#, Rust, and the creation of CAD applications.

Obligations Link to heading

Something I’ve found is that when someone starts to pay you to do something you enjoy, it stops being fun and turns into work. I think the reason this impacts motivation is two-fold.

For one, when you are being paid to do an activity you once did for fun, you change from intrinsic motivation (doing it for the sheer enjoyment) to extrinsic motivation (doing it for the money). As someone who doesn’t respond well to extrinsic motivators (e.g. I did well at school because I enjoyed the content, not because I wanted the marks) being given money isn’t a big motivator.

Another aspect to this is you now have commitments and obligations to other people. If I don’t complete a task I’m being paid for on time, there are repercussions. For example, the product timeline may blow out, or my coworkers might be forced to pick up the slack. On the other hand, when you are doing a project for your own enjoyment, nobody cares if it gets forgotten after a month or goes nowhere.

I’ve always been quite conscious of this, so although I’m employed as a full-time software engineer I try to make sure the languages and frameworks I use in my personal time are completely unrelated to what we use at work.

This feels like a good compromise. I get to maintain a strict distinction between work and play, while also being able to use the skills I develop at home to solve problems at work.

Sturgeon’s Law Link to heading

Sturgeon’s Law is an observation about the world, often paraphrased as

Ninety percent of everything is crap.

This phenomena can have a pretty big impact on your motivation. For example, a lot of the code I’ve seen (written by others, of course) falls into that 90%.

It feels like a lot of people learn the basics of programming and decide to commercialise it without really learning how to design large projects properly, so they end up flailing about until they’ve added enough global variables and if-statements that the thing kinda works.

I normally wouldn’t care less if your code is a pile of 💩 under the hood, you’re doing something you enjoy and trying to create a product which will give others value so more power to you.

However, when you inflict that 💩 on me, it can really impact my motivation levels (e.g. I inherit your codebase and it’s the second month of debugging in production trying to track down a spurious, mission-critical bug which is actively costing customers money because you designed a communication protocol without knowing how to design a communication protocol). And the thing about motivation is that once lost, it tends to take a really long time to come back. Even after the original problem has gone away and things have returned to normal.

This trend of the vast majority of things being crap can also be quite humbling in a way.

When I look at the list of repositories I’ve created on GitHub or GitLab I see a large number of half-baked ideas and failed projects. Although I’ve learned a lot from each of them and enjoyed the creation process, I’m sure quite a lot of it is crap.

It also really makes you respect the people who build good quality things.

For example, the serde serialization framework is easily one of the most expressive and user-friendly serialization mechanisms I’ve used so far.

Another project I’m a big fan of is uom, a crate for working with systems of units in a type-safe manner. When you’re modelling mechanical devices it’s amazing how useful it is to have the compiler yell at you when you accidentally try to add a speed to an acceleration.

For me, seeing high quality projects like serde and uom is an inspiration

to also go out and make nice things.

Conclusions Link to heading

I don’t think there’s any one factor which affects a person’s motivation. Like a lot of things in the real world, it’s complicated, and despite what the self-help industry would like you to think, there is no 5 step recipe to increase your motivation levels.

That said, this was still an interesting little exercise. Normally I’ll find a highly technical topic to do a deep investigation into, so it’s nice to have a change of pace every now and then. Also, the whole idea of thinking about thinking is meta enough to be appropriate for this blog.

Something else I neglected to look into is burnout. I’ve been burnt out before so am fairly confident the recent low motivation isn’t caused by burnout, but who knows?